"Picturing Temperament" is a pictorial method of looking at musical temperament. In all my other articles on this subject, I've demonstrated through sheet music, the harmonic series, and written out Hz frequencies. I kept thinking that if I could just put it on a ruler, the visual would be much better, especially for non-musicians. There are lots of "temperament wheels" out there that show temperament using the 12 numbers of a clock. That works somewhat but it's a bit more difficult to compare and contrast temperaments using a clock. Here, we'll look at a variety of musical temperaments on a ruler.

What exactly is temperament? Musical temperament adjusts the distance between notes. Temperament adjust the "intervals" within a scale. In equal temperament, the distance between every note of the scale is exactly the same. All other temperaments have slight variations within notes (intervals) of the scale. The one true constant is that octaves are always "pure" which simply means they are perfectly in tune and are exactly doubled. EX: 220 Hz, 440 Hz, and 880 Hz are Perfect octaves of one another. To get an octave higher, double the Hz number.

We begin by looking at a ruler with the note names at the top. You'll notice that I've made the note names the colors they represent when translating nanometers to Hz.

Figure 1

Notice that the distance between every line on the ruler is exactly the same. The tallest lines represent the name for each of the twelve notes of the scale in Equal Temperament. Rulers have exact and equal measurements just like Equal Temperament. ALL other temperaments have slight variations from Equal Temperament.

The temperaments I'll discuss in this article are:

- Equal Temperament

- Just Intonation

- Pythagorean Tuning

- Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies (not a temperament but here for comparison)

There are MANY more temperaments available but the above three are the ones most familiar to the general public in the 21st century. Had you lived in the baroque, classical or the early part of the romantic era, instrument makers and musicians chose their preferred temperament and concert pitch. In other words, there are way too many temperaments to name in this article.

It wasn't until the industrial revolation that we had a way to measure musical pitches (in Hz). It was at that point, equal temperament was born. Yes, there was a form of it used earlier (well temperament) but it wasn't perfectly equal since all tuning was done by ear, not machine. Those who would argue Bach created equal temperament need to look no further than his own writings. He wrote the "Well Tempered Klavier," not the "Equal Tempered Klavier." Bach was the first famous musician to come up with a plausible solution to continual tuning issues by creating a temperament that sounded great in some keys and a bit more "crunchy" in others. His version of temperament allowed musicians to play in all 24 keys (major and minor) without retuning for the keys using lots of sharps and flats.

We forget that composers like the crunchy and slightly dissonant chords and intervals at times. It creates the "tension and release" required to bring emotion into music. If you look at this the way Bach did, knowing that certain keys (Ab, B, F#, C#, and Db) were going to be more out of tune than keys with less sharps/flats in well temperament, it might help music theorists discover a deeper level of understanding as to why early composers chose certain modulations and key changes. We'll leave that topic for another discussion.

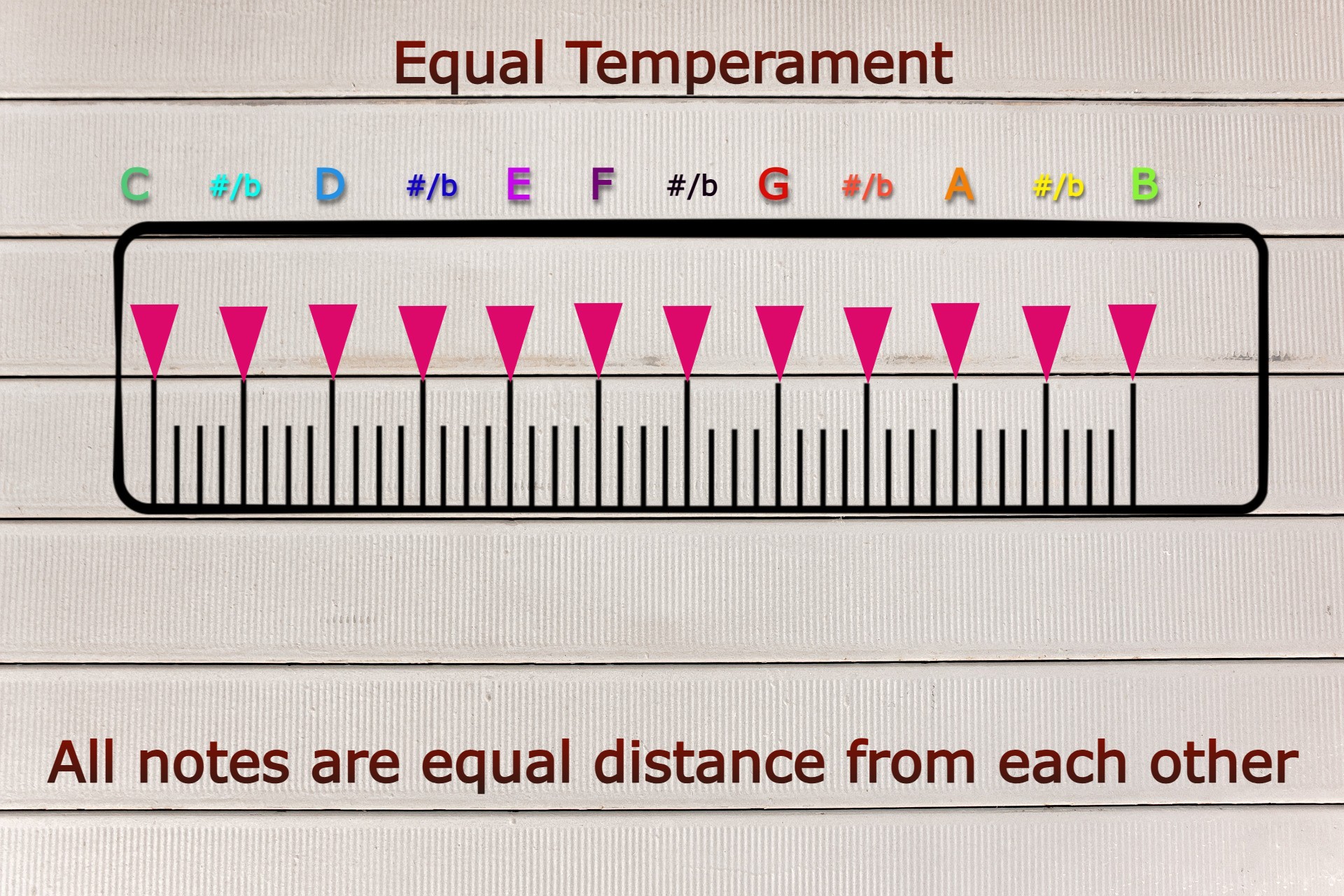

Now, let's look at equal temperament on a ruler (Figure 2). Notice the pink triangles are pointed directly TO the longest marks on the ruler. They are equally spaced which indicates equal temperament.

Figure 2

Pythagorean Temperament (Tuning)

Most everyone knows the story of Pythagoras hearing blacksmiths pounding hammers on metal where he could hear different pitches. Although we attribute the discovery of ratios to Pythagoras, there's evidence "ratio tuning" was used well before Pythagoras' time. In museums, we have the silver lyre of Ur from about 500 years before Pythagoras, the Zeng Bells of China, from the time of Pythagoras, and some bone flutes that are dated anywhere between 20,000 to 40,000 years old. There are videos of people performing on replicas of these instruments and they sound very similar to our modern versions of both Western and Eastern scales.

Pythagorean tuning focuses on ratios of the intervals within the octave. Those ratios are:

- Perfect Octave (P8) 1:1

- Perfect Fifth (P5) 3:2

- Perfect Fourth (P4) 4/3

- Major Second (M2) 9/8

- Major Third (M3) 81/64 and is quite sharp

- Minor Third (m3) 32/27 and is slightly flat

There are others but at that time, sharps and flats were used sparingly because they were so out of tune with the other intervals. I did not put Pythagorean tuning on a ruler because it's quite close to Just Intonation.

Just Intonation

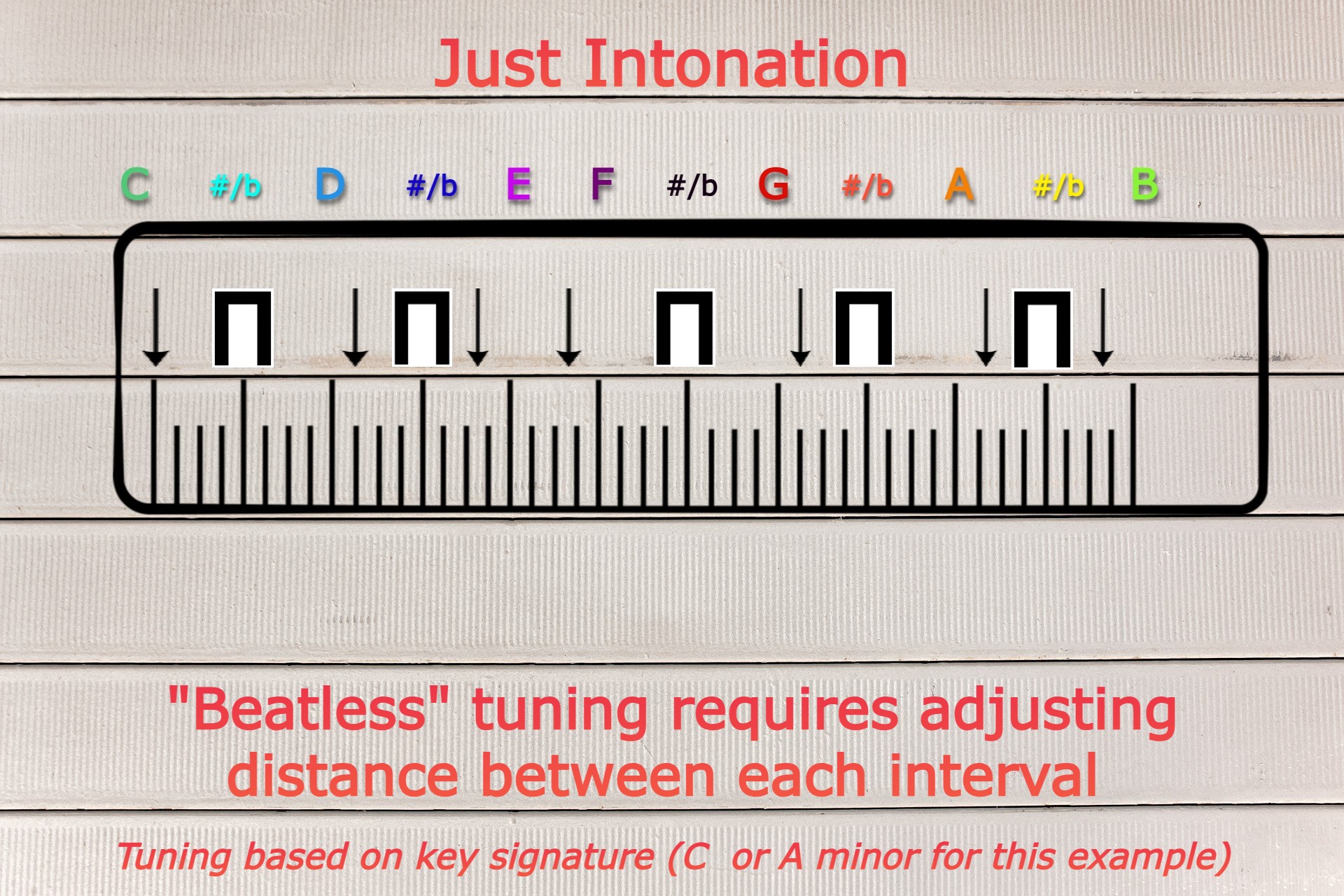

Figure 3 shows my ruler with the general tuning for Just Intonation for music in the key of C Major or A minor. Remember that the longest marks represent equal temperament because they are equal distance from each other, as seen in Figure 2. Temperament changes the distance between notes. Therefore, in Just Intonation, some intervals are wider than others.

The arrows in Figure 3 point to approximately where the "Just" scale would fit in the key of C Major/a minor. Some notes are to the left of the tallest marks on the ruler and others are to the right. The further apart the marks are between each other, the larger (wider) that interval is. The same is true for marks that are closer together. Those intervals are smaller (narrower).

The staple marks show the black keys as two different pitches depending on whether you're approaching the sharp/flat note from above or below. Just Intonation is how most string players (non-fretted) perform without even knowing it. Good singers and wind players do the same. Honestly, unless you're in a group with ONLY keyboards and fretted strings (guitars), good musicians can adjust intervals as needed so they're in tune. Therefore, Equal Temperament only exists within keyboards and fretted instruments. Wind and non-fretted string players (as well as good singers) rarely stay within Equal Temperament.

Figure 3

NOTE: Just Intonation is quite close to Pythagorean tuning and many other temperaments until equal temperament came along. There are slight differences but not enough to create a Pythagorean ruler. Most people would only be able to detect a slight difference between a Just and Equal Tempered scale. The major difference is between notes 6, 7, and 8 (the octave) of any scale. This is NOT the case with the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies, which are presented after Figure 3.

Just intonation became popular once keyboards and fretted strings were invented. By then, musicians were creating more complicated music which required the use of sharps and flats and not just the white notes on the piano. In the Renaissance era, they introduced "musica ficta" which added F# and Bb so musicians could avoid the dreaded tri-tone. In their mind, the tri-tone was the "devil's interval" and should always be avoided because it was so dissonant to their ears. They were used to "pure" (beatless) intervals, which is another reason they rarely used the Major 3rd in the Medieval era.

Just Intonation required that musicians perform music in sets where keys were similar. For example, the keys of C, G, and D, could generally use one tuning. Once the tunes in these keys were performed, the keyboard and fretted instruments would be retuned for music with more sharps or flats. Just intonation gives the performers license to tune the intervals so they're as "pure" as possible. Some early keyboards even had two black keys - one for F# and another for Gb. Depending on whether you approached the sharp/flat note from above or below, determined which black key you used.

If your mind is spinning right now, join the club! These very problems are why we now use equal temperament. NEWSFLASH!!! No temperament is perfectly in tune. Good musicians learn to adjust tuning on the fly as they perform. Well, that's everyone but those who play piano and fretted strings.

Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies

The ancient solfeggio frequencies do not fit within any temperament known by musicologists and/or reliable music historians (people who read music and understand music theory). The Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies are included here because people continually want me to speak about them. Therefore, I'm going to show you visually how they fit on the temperament ruler. You'll see the drastic difference between these frequencies, Just Intonation, and Equal Temperament. There's a separate article coming with more pictures for the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies.

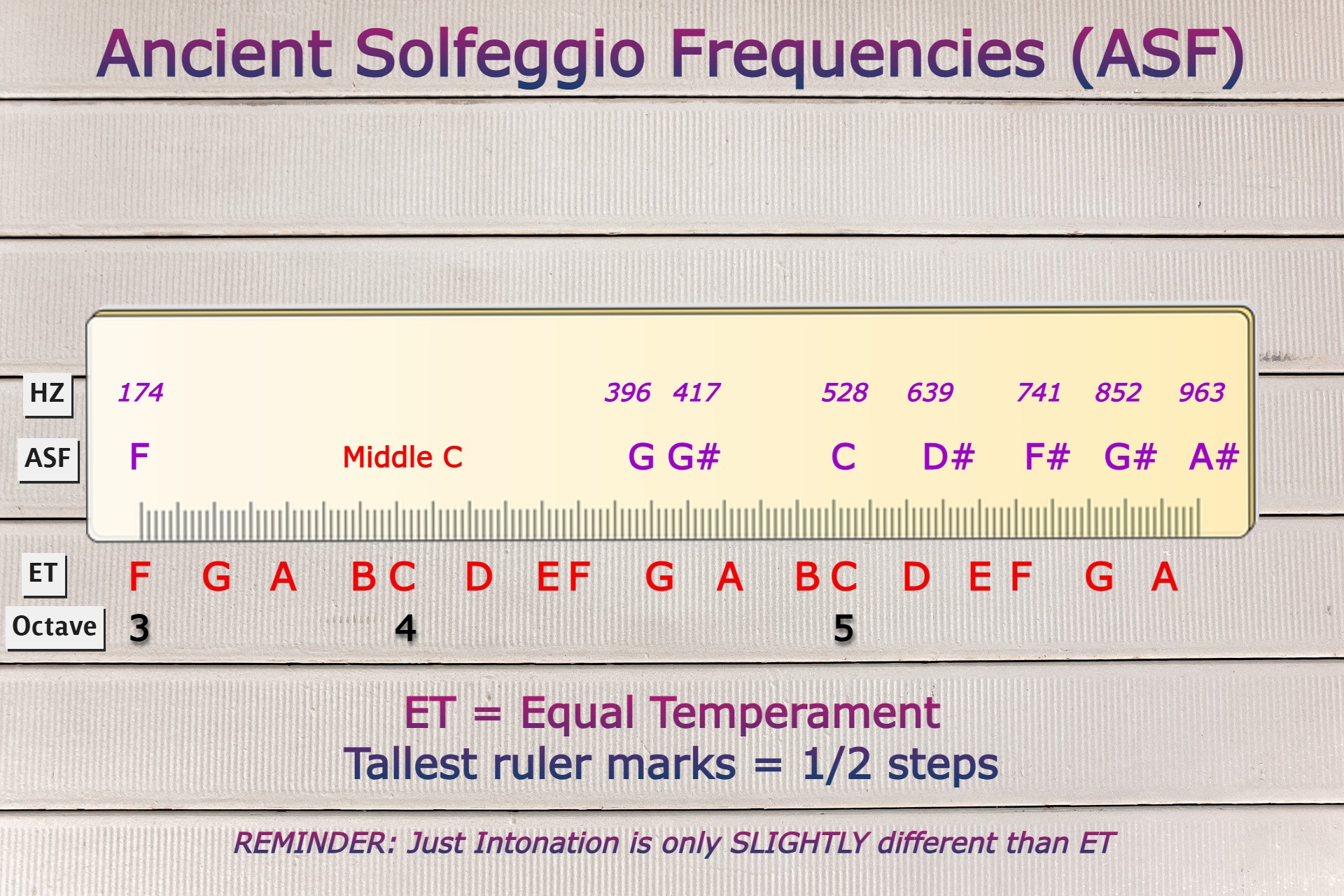

We'll start with some basics by putting all three sets of pitches in three separate groups according to their numbers:

174 = F3 (sharp)

417 = G#4

741 = F#5 (flat)

285 = C#4

528 = C5 (sharp)

852 = G#5

396 = G4

639 = D#5

963 = A#5 (very sharp)

We immediately see the pattern is simply taking the last number and putting it at the beginning for the second number, which is repeated for the third number. This is the only obvious pattern.

It's quite easy to see by putting the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies on the ruler in Figure 4, there is no MUSICAL pattern, they don't fit close to any temperament, and they definitely do not create a scale. NOTE: The 174 Hz and 285 Hz are often NOT listed as part of the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies (ASF). However, because we're looking at patterns, I added them in to see where they would fit on a keyboard.

With this evidence, I've proposed in many articles that the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies are more than likely related to another form of moving energy that's not musical. Yes, any Hz frequency can be used as a musical frequency because your INTENT is always part of the recipe. If you believe it will be helpful, then it will. But, are the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies based on music? Credible evidence and the natural laws of the universe appear to show us that we're missing something when it comes to the actual purpose of these three sets of numbers. Might I suggest that a starting point is to Google the Rodin Coil. I suspect these numbers have more to do with the toroidal field and how it moves energy.

See Figure 4 for placement of the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies on the Equal Tempered (and close to Just Intonation) ruler.

There are four rows:

- Hz = the Hertz frequency

- ASF = Ancient Solfeggio Frequency

- ET = Where Equal Temperament (and closely related Just Intonation) sit on the ruler.

- Octave = Which octave on the keyboard it represents

Figure 4

In the upcoming article for the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies on a ruler, I demonstrate how to tune a guitar or keyboard to them. If you're wanting to make sure your tuning is exact, you must tune each frequency separately. Then, create music based on the one frequency. Retune for the other frequencies and repeat. Sorry, but they won't work together with one tuning. That article will be available in September of 2025.

Conclusion

One thing we've learned throughout history is that musical temperament was mostly based on personal preference, until the introduction of Equal Temperament in the 1800's. There were still a variety of different concert pitches out there but, equal temperament was here to stay, or was it? I beg to challenge my own question because even with Equal Temperament, good wind and string (non-fretted) musicians adjust as needed. Non-fretted instruments include violin, viola, cello, and bass. There ARE some bass guitars that are NOT fretted. All other guitar-like instruments (Western tradition) are fretted.

As I stated in the first paragraph of this article, unless you're playing a piano, keyboard, or fretted instrument, you can adjust temperament mid-performance. Prior to the 1800's, keyboard players had to stop and retune according to the keys within the music. This is one reason why the extreme sharp and flat keys were not used in the Renaissance era - they were too difficult to tune. That is until Bach came along with "well temperament" and his Well Tempered Klavier. Anyone who has ever studied classical piano knows this music well.

How does this all fit within the natural laws of music?

I watched a video where Dr. Robert Gilbert compared the Pythagorean comma (out-of-tuneness in music) with fractals. He said that the "Archetypal blueprint for creation that exists on a higher plane level manifests down through multiple planes until it crystallizes that pattern into physical structure. There's often a slight incongruence between the perfect idea form and how it manifests on the physical plane. The Pythagorean idea and everything in the physical world is a little bit off its actual archetype but in Egyptian tradition, it was understood that slight imperfections make things completely unique."

The Pythagorean comma has a built in gap or slight imperfection that makes music unique and beautiful. Both dissonance and harmony are present in music. It fits the other patterns in nature set at the beginning. The Pythagorean comma is nature's blueprint for music. Even in its slight imperfection, it's beautiful. Sometimes those imperfections are needed so adjustments can be made within the blueprint as needed to create a balance between dissonance and perfect harmony.

The comment by Dr. Gilbert proves that the natural laws of music allow for adjustments. He demonstrated this when discussing the "Pythagorean comma." Therefore, no tuning system is perfect because individual people make adjustments according to individuality, desires, and how they want something to sound. It's been that way throughout recorded history.

Enjoy the music you love and don't worry about what concert pitch, temperament, or tuning system was used in the creation of that music. Choose what works for you and INTEND the music is helpful for your being - spirit, soul, and body. However, if bad lyrics are involved, choose new music with words that better align with a more positive intention.

Del, August 2025