Picturing he Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies is another way of comparing these frequencies spacially - both on a keyboard and a ruler. When we see a frequency written out and can't put it into context, it's hard to figure out how it compares to other frequencies. If I've learned one thing on this journey, it's to look for patterns. Therefore, I find a variety of methods to demonstrate patterns. In this article it's with a ruler and a piano keyboard. At the end, I'll show you how to tune to these frequencies if you want to use them. I've done so in other articles but here, that process is more specific.

Everything in the cosmos is based on patterns (ratios, math, harmonics, equations, cycles, etc.) As I've said in previous articles, when you find a pattern, keep going further down the rabbit hole. When the pattern stops, put stuff on the shelf for another time in case you missed something the first time.

Although I've written about the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies in other articles, this version is specifically for those who prefer visuals. And, I include some new information as I've continued to research. For people who don't read music or understand music theory, hopefully my pictures can help you visualize what the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies might sound like - spatially. Even if you're a musician and use these frequencies but haven't looked up their specific notes, this will help you!

Let's start with what we've been TOLD about the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies:

- These frequencies were first spoken about by Joseph Puleo in the late 20th century.

- Puleo stated they are lost frequencies and first discovered by Guido d’Arezzo where he found a secret code in the book of Numbers (from the Bible).

- Puleo also said the true solfeggio scale was created by Guido d’Arezzo (1,000 AD) and that we’ve corrupted it.

- The tones are said to be in the Hymn to St. John the Baptist and that they create a scale.

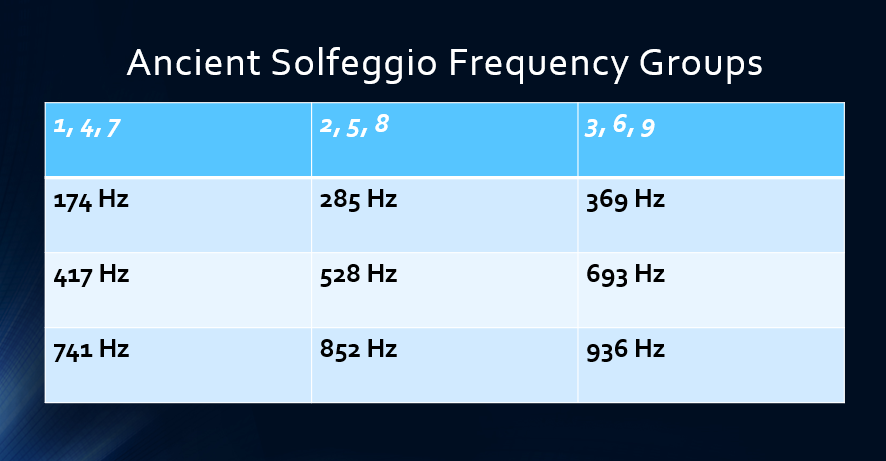

Figure 1

In figure 1, you'll notice that when taking the three sets of numbers and grouping them together, there IS a pattern. NOTE: The numbers 174 and 285 aren't included with most versions of the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies. They are here so you can see the pattern. The pattern is as follows, 174 starts with a low number. Move the 4 to the beginning to get 417. Then, move the 7 to the beginning for 741. Repeat the process for the remaining two groups. At this time, it's the only pattern that I can find but one interesting item to note is that the numbers 3,6,9 align with a quote by Tesla. “If you only knew the magnificence of the 3, 6 and 9, then you would have the key to the universe.”

The Hz numbers most often described as being associated with the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies are: 369 Hz, 417 Hz, 528 Hz, 693 Hz, 741 Hz, 852 Hz, and sometimes 963 Hz. The range of notes these frequencies represent is an octave plus two notes (852 Hz and 963 Hz). When using only six notes (369 Hz through 852 Hz), the span is from G5 to G#5 - a half step larger than an octave.

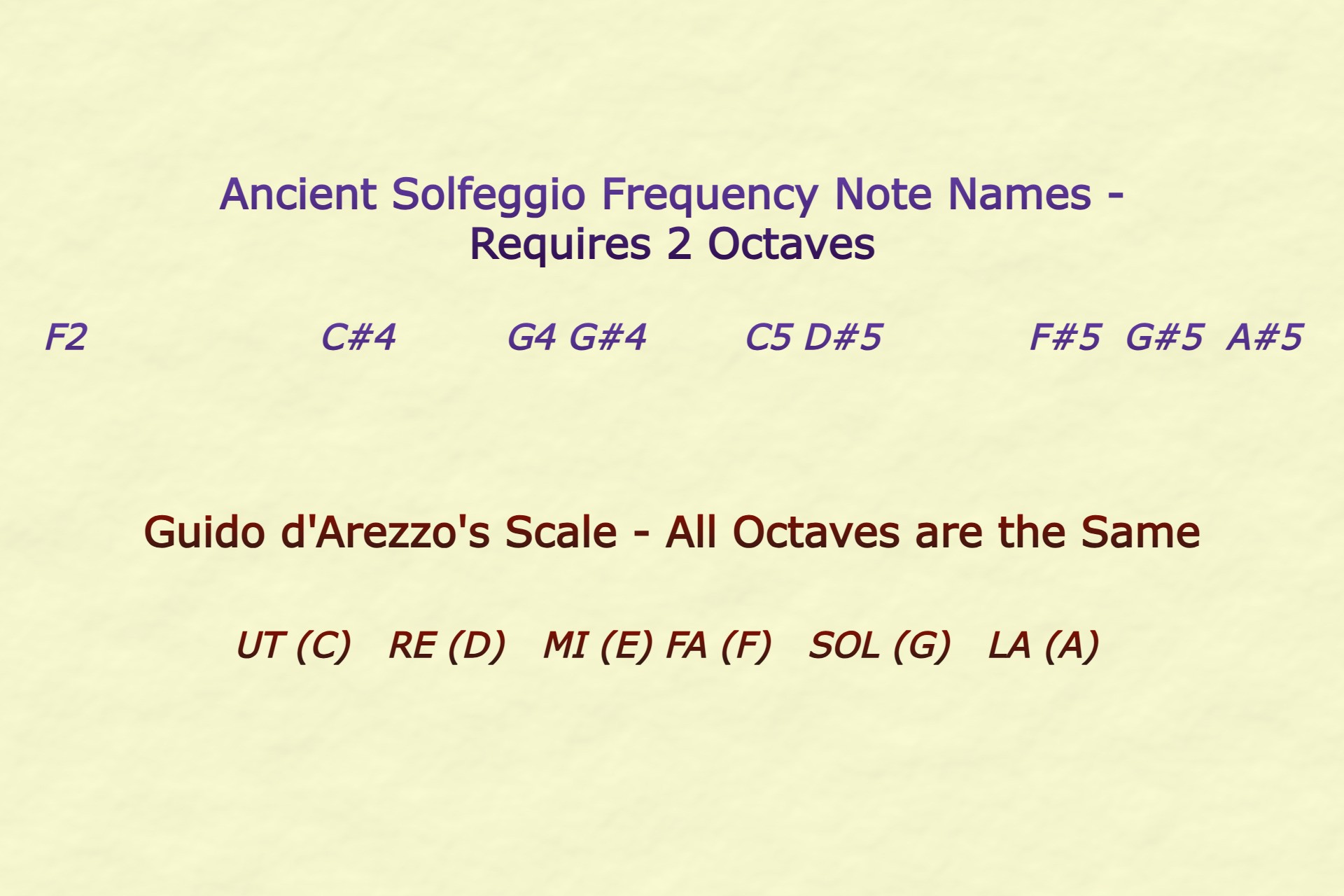

Next, we'll look at how all the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies (all 9 numbers) line up with the actual scale Guido d'Arezzo wrote. (Figure 2)

Figure 2 shows the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies at the top and Guido's scale at the bottom. At first glance, it's easy to see the two aren't similar. Guido's scale fits nicely within one octave. The Ancient Solfeggio Frequency Hz numbers span nearly 2 octaves.

Figure 2

Keep in mind that Guido d'Arezzo is the one who invented sheet music. Once he came up with a method of writing down the chant repertoire, he began the process of teaching the monks how to read the music. For that, he used "Solfege" or "solfeggio" as some call it. The monks learned how to read music which cut the time of learning the chant repertoire down by more than half the time! Prior to having sheet music, it took the monks nearly 10 years to learn all the chant repertoire.

Our modern method of solfege was developed by Zoltan Kodaly and is a popular method of teaching music reading and "sight singing" in elementary schools. All music schools use solfege for training musicians to learn a piece of music without hearing it first simply by singing the solfege instead of lyrics or pitch names (with no accompaniment). If you've ever heard the song Do, Re, Mi for the "Sound of Music," you know what solfege is. Click to the title to hear it.

Joseph Puleo said the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies are found in a hymn and that they create a scale. The hymn is below and it's not difficult to see that the notes represented in the Ancient Solfeggio "scale" are not even close to Guido's original solfeggio.

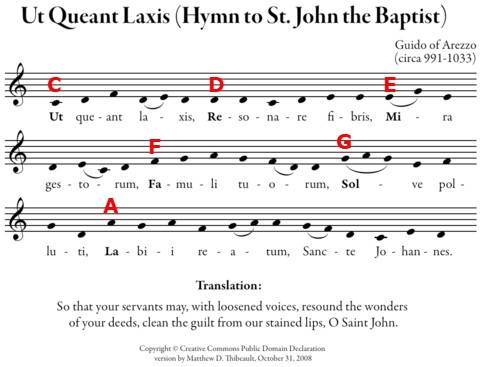

Figure 3

Figure 3 shows the music Guido used to help the monks learn solfege. Notice that I added the modern note names above the main solfeggio notes so you can see that they ascend in a stepwise pattern. The notes are close together and stay within the octave. At the time of Guido, the "Ti" (B) wasn't yet added. That came a little later.

Read the lyrics in Figure 3 and notice the bold notes begin with the solfeggio names (Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La). Based on my music training, this helps the singer solidify the distance (interval) between pitches. The singer learns to correctly sing each note where it's supposed to be placed. In the music above, most intervals are Major 2nds (M2) and minor 3rds (m3). At the end of line 2, the first minor 2nd (m2) appears and in the final line, there is a Perfect 4th (P4) followed by a Perfect 5th (P5), more 2nds and then within the last three notes, the Major 3rd (M3) is introduced. It's important to remember that the monks didn't have instrumental accompaniment so there was generally no "starting pitch" given. Therefore, understanding intervals was very important.

Let's compare the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies to the musical scale introduced by Guido that's also been around since before the time of Pythagoras. It's the same scale that was used by Guido, minus the note, "B." Many early musicians avoided B so the dreaded tri-tone (F to B) couldn't be used. Eventually, "musica ficta" was added to solve that problem. Later musicians added the notes B, Bb, and F#. Key signatures were born (Medieval to Renaissance eras).

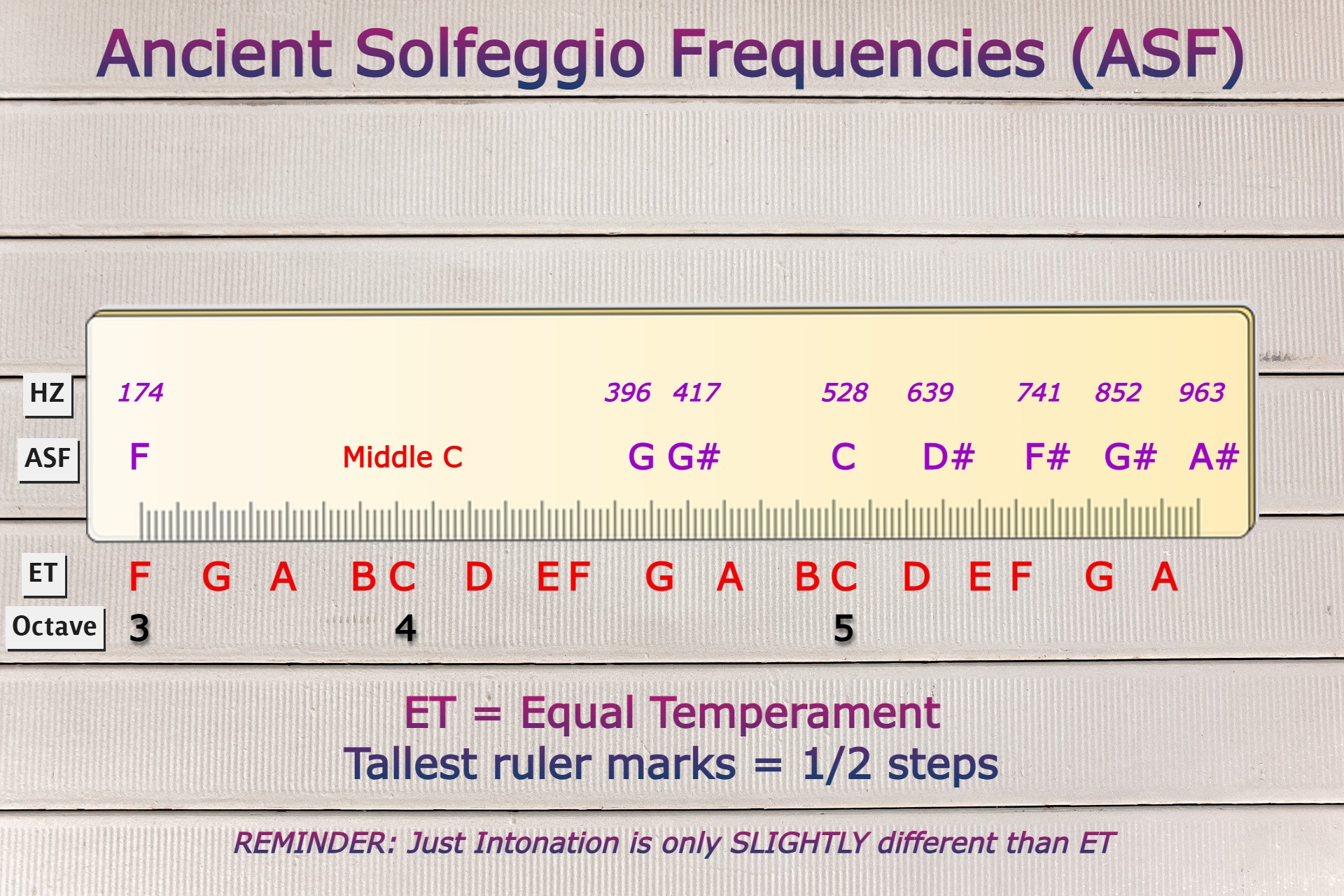

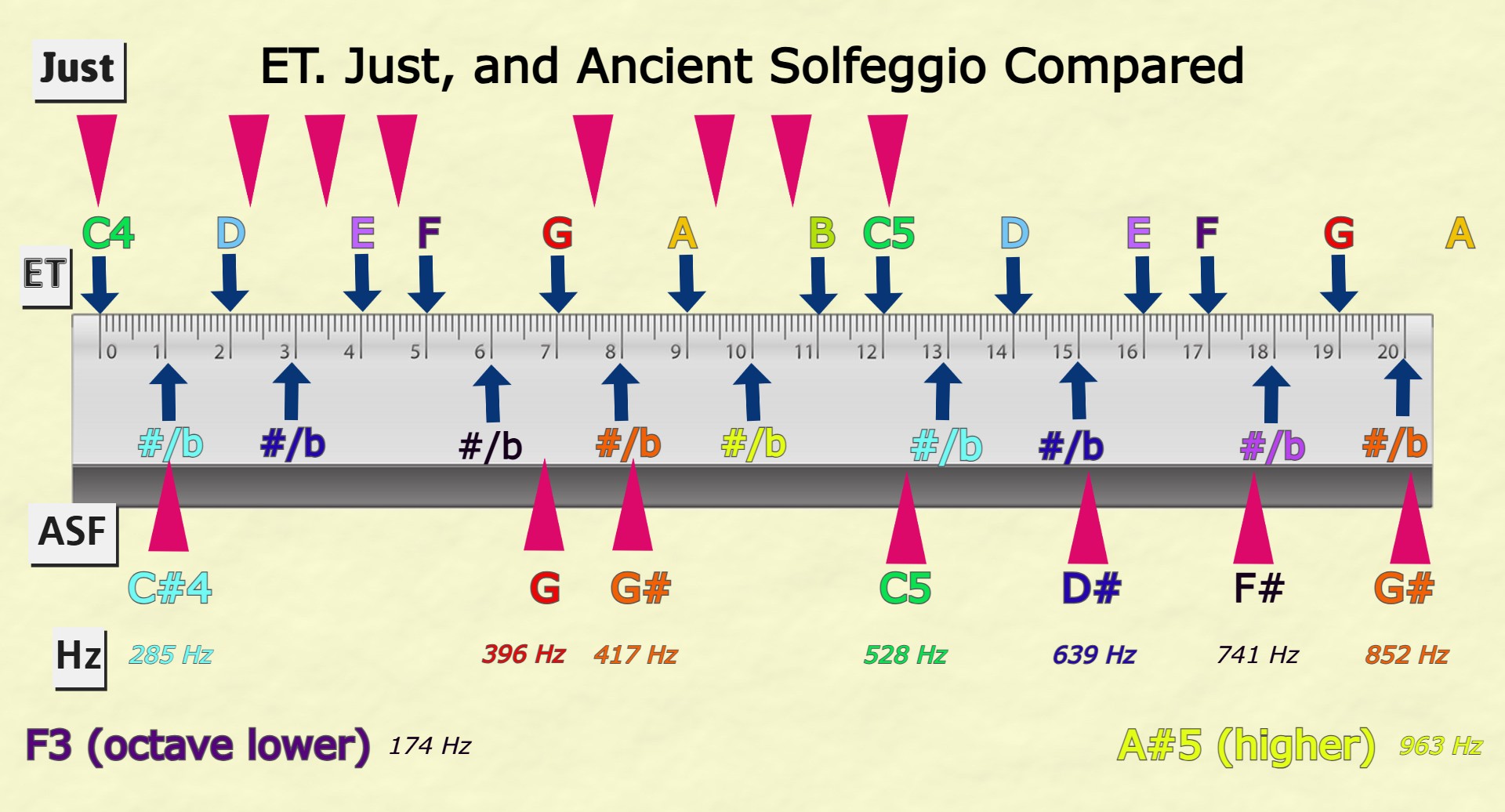

Figure 4 demonstrates how the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies compare to Equal Temperament on a ruler. Equal temperament (ET) is where the distance between every 1/2 step is exactly the same. It's close enough to the tuning Guido used that most people might only hear slight differences between ET and the natural scale of Guido's day. It all depends on how good your ears are.

Figure 4 demonstrates two things: our modern equal tempered scale (close to Guido's) in red and the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies in purple. They can't be called a scale because as you can tell, there are missing notes. The ONE similarity between ALL historical scales and tuning systems? The octaves are always pure.

Figure 4

Look at the G#4 at 417 Hz and the G#5 at 852 Hz. Every tuning system (temperament) has at least one constant - octaves are "beatless" and Perfect. They are an exact doubling of lower octaves. Let's take the two G#'s from the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies (417 Hz and 852 Hz). 417 Hz multiplied by 2 = 834 Hz. To have a pure octave, the upper G# would need to be 834 Hz, not 852 Hz. The two pitches are 18 "cents" apart, which would cause a noticeable beating pattern that makes the two notes sound out of tune when played together. This alone tells me these frequencies are probably related to something other than music.

Two patterns have already been broken: 1) the law of octaves and 2) the law of harmonics (which is how scales are built).

Figure 5

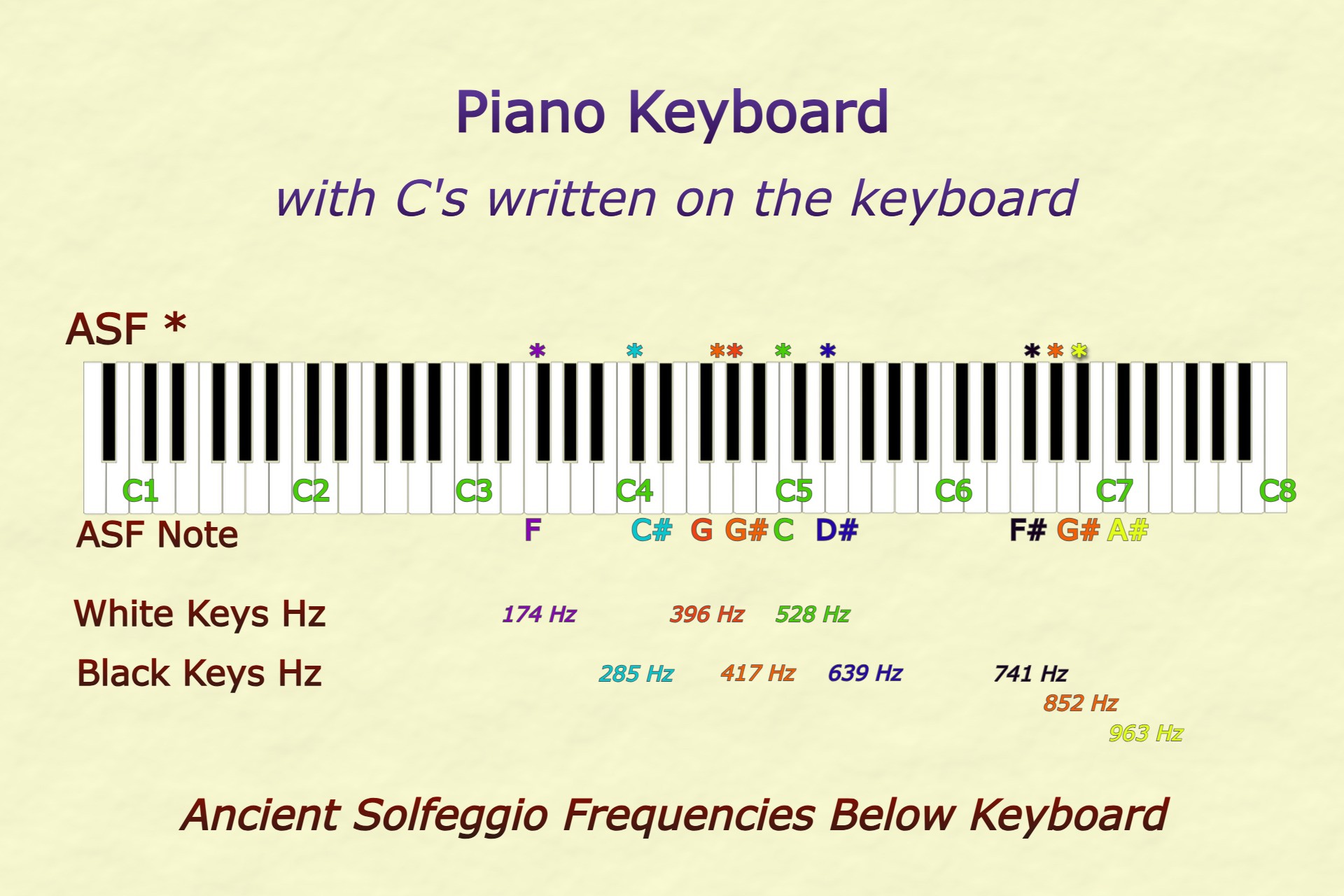

Figure 5 shows a piano keyboard where all the equal tempered C's are marked (in green) with their appropriate octave number on the keyboard. The Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies note names and Hz numbers are listed below the keyboard. A star (*) is placed just above the keyboard so you know which key it's referring to.

NOTE: When taking nanometers down to Hz, a color can be given to a musical note. The colors represented by all frequencies in Figure 5 correspond to their color "family." Just like green has a variety of different colors in the green tones, each musical note will have a different sound when the pitch goes up/down. That's one reason all the C's are green, the G's are red, the B's are yellow, etc. in Figure 5.

Without going into a lot of musical detail, simply look at the comparison between the keyboard note placement and the Ancient Solfeggio Scale. Remember that our modern pianos are tuned to Equal Temperament (ET) as you'll visualize on the keyboard. ET means all half-steps have equal distance between them. Modern tuning is similar to "Just" intonation which and Pythagorean tuning. The main difference is the distance between notes is adjusted (temperament) but the intervals are still the same (M2, m2, M3, P4, P5 etc.). But... they will SOUND slightly different to a good ear.

Compare how ET, Just, and the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies compare in Figure 6.

Figure 6 shows the Just Intonation scale at the very top with pink triangles pointing down, the Equal Tempered (ET) scale in the middle with dark arrows, and the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies (ASF) on the bottom with pink triangles pointing up. It was hard to find a ruler long enough so you'll notice the F3 and A#5 in the ASF are lower and higher than the ruler.

Figure 6

The pink triangles in Figure 6 represent pitch placement on a ruler for Equal Temperament, Just Intonation, and the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies (ASF). I use the Just Intonation temperament because it's the most natural tuning used since ancient times. Yes, it's a variation on Pythagorean temperament but the differences are slight. Good singers naturally tune themselves via Just Intonation. We see this was the case as well with ancient instruments. See the Picturing Temperament article for the instrument details.

The dark arrows directly on the ruler facing down represent the white keys on a piano with their appropriate colors. The dark arrows facing up are the black keys with their appropriate colors. Equal Temperament measurements are exact, just like a ruler is exact. Everything is equally spaced so musicians can play in all keys without retuning their instruments. This isn't a problem for singers and since Guido's monks sang the chant music without instruments, temperament wasn't an issue.

Notice that the Just Intonation pitches vary in the distacne between notes (temperament). For example, the distance between C - D is wider than the distance between D - E. There is a tuning reason for this, which I won't get into for this article. To this point, we haven't yet discussed concert pitch. You'll want to read the Picturing Concert Pitch article to better understand how it works, which comes into play with the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies.

Conclusion

As I've said in many previous articles, if you like using the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies, continue doing so. Some of the frequencies work well with the A=444 concert pitch but other's don't. Therefore, if you're a musician and want to use them, you'll need to retune your instrument for each frequency. Use the Hz number as your starting pitch and tune your instrument to that frequency. You're setting a new concert pitch to a specific Hz number. For example, G=396 Hz, or G#=417 Hz, or C=528 Hz, etc. We'll go over how to do that at the end of this article.

Here is what we've learned about the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies (ASF) in this article:

- The ASF don't fit within the laws of music (harmonics, pitch structure, and tuning).

- The ASF don't fit within the "law of octaves" either. Two of the notes are supposed to be octaves of one another (417 and 852) but they're off by 18 "cents."

- The ASF cover nearly two octaves with only 9 notes. This doesn't match any historical instruments found in either Western or Eastern cultures. See the article on the Zeng Bells of China from the time of Pythagoras to see and hear variations of tuning practices from WAY before Guido's time.

We forget that intention is a HUGE part of how we perceive something. The key point here (no pun intended) is that if you LIKE music created using the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies, then listen to it with the intention that you'll get something out of it. After all, I've even created music using the 528 Hz frequency because people asked me to, and many people believe that frequency carries healing properties. Notice... people "believe" so there's the intention and an ingredient in a wholeness recipe. This simply shows the power of intention. Imagine how life would change if we focused more on the positive rather than all the negative junk going on around us? Hmmmm....

After several years of looking deeper into the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies, I believe they are related to moving energy in some manner other than as musical frequencies. It seems they have a different purpose that would create a stronger result when used as they were intended. I have yet to figure that out but I suggest that if you're curious, go look up the Rodin Coil and see if that makes sense to you. It has something to do with moving energy in a toroidal motion, which is quite interesting. That's another rabbit hole to go down for another day.

Enjoy music created with the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies if that's what you enjoy listening to!

Creating Your Own Music with the Ancient Solfeggio Frequencies

If you want to tune your guitar or keyboard to these frequencies, you'll need to use each note as the "concert pitch" by tuning that specific Hz first. Sorry, wind instruments are not able to do this other than the 528 Hz frequency. Tune the other notes to that specific frequency. Only more expensive keyboards have a feature that allows you to adjust concert pitch.

BEING EXACT: Because the Hz numbers won't be exact in any concert pitch (including A=444), you'll want to tune EACH Solfeggio number when you decide to create with it. This means you can only create songs per frequency. Sorry... but because they aren't consistent to any temperament or concert pitch, this is the only way you'll truly get the Hz numbers to match exactly.

NOTE PLACEMENT REMINDER: The 4th octave begins at middle C up to 4th line B on the treble clef. 396 Hz and 417 Hz are above middle C in the 4th octave. The 5th octave begins with 3rd space C, an octave above middle C. 528 Hz to 963 Hz are in the 5th octave from 3rd space C (528 Hz) up to the A# (963 Hz) above the staff.

- You'll set the "concert pitch" for each frequency by using THAT frequency as your starting pitch. For example, if you want to focus on 396 Hz, you'll need to tune the G above Middle C to 396 Hz and then tune the other strings FROM that string. Do NOT use your tuner for this process. Use your ears and tune the intervals!

- Pull out a tuner that measures specific Hz numbers (or use an online tuner). You need to be able to see the Hz number register when you set the tuning note (concert pitch).

- OPTION 1: Guitar players, if you want to tune to a lower octave because of string placement, take the higher frequencies and keep dividing by 2 until you get the desired lower octave. For example, 963 Hz divied by 2 = 481.5. If you want an octave lower than that, divide 481.5 by 2 to get 240.75 Hz. This makes it easier to tune the lower strings. You need to be exact!

- OPTION 2 is to set the Hz number on your tuner and listen to it so you can hear the frequency, then find where that note is on your instrument, and tune your instrument to what you hear on the tuner until there is no "beating" between the two pitches. However, this is the less preferred option because you may not get the exact frequency with your ears.

- Keep playing the Hz note in the correct octave on your instrument as you change the dial on your keyboard or adjust string tension on your guitar until the tuner reaches the appropriate Hz number or it sounds in tune.

- Guitar players, next tune the remaining strings to your new concert pitch. Do NOT use a tuner for this part! Use your ears please if you want the intervals to sound better.

- Keyboard players, the change will be automatic because the instrument is already set in equal temperament. All other notes will automatically be adjusted to your set concert pitch. Only newer and more expensive keyboards with "weighted" keys have a feature that adjusts concert pitch. Please ask your sales representative before purchasing an instrument if this is important to you! If you need assistance, call Sweetwater and ask for their keyboard department. Tell them I sent you!

Please be sure to check out the Healing Frequencies Music YouTube channel for the corresponding video that will come out after this article is posted. If you subscribe to the channel, you'll be notified when that video drops. Once it's up, I'll come back to this post and include a direct link.

If you have questions, the best place to ask them is below the corresponding YouTube video. I always read comments and respond as quickly as possible.

Del, September 2025